Although military conflicts have long plagued Africa’s Great Lakes region, the relationship between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda, its eastern neighbor, saw a significant shift in 2025.

- Conflict in Eastern Congo escalated in 2025 with attacks by the M23 rebel group on Goma, prompting international condemnation.

- While Angola and other mediators failed initially, Qatar facilitated renewed dialogue between representatives of Rwanda and the DRC.

- U.S.-brokered discussions led to the establishment of a Joint Oversight Committee in Washington, marking a diplomatic breakthrough.

What began as another tragic chapter in the ongoing instability of eastern Congo escalated into a full-blown geopolitical crisis, culminating in a series of peace talks that may yet redefine the region’s future.

M23’s offensive in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Conflict flared up again in January 2025, when the M23 rebel group, long suspected of getting help from Rwanda, launched a concerted attack on Goma, a crucial city in eastern DRC.

The onslaught was savage and swift, killing hundreds of civilians and causing significant displacement.

Within days, more than 900 dead were discovered on Goma’s streets.

The world condemned Rwanda, and it came under tremendous scrutiny for its alleged involvement in the attacks.

Despite Kigali’s denials of complicity, regional and international players imposed sanctions and threatened economic repercussions.

A path to peace following weeks of bloodshed

In early February, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi attended a joint conference of Eastern and Southern African leaders in Tanzania.

The event was held in reaction to the escalating violence, which had resulted in a humanitarian crisis.

Despite M23’s unilateral ceasefire, their advance into Bukavu in South Kivu continued, demonstrating the fragility of any informal agreements.

Recognizing the urgency, both the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the East African Community (EAC) intervened.

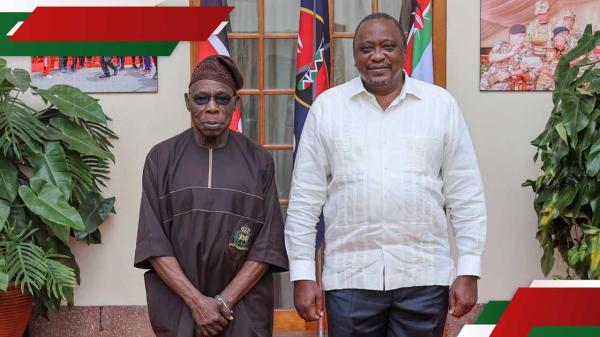

In a significant display of solidarity, they nominated three African politicians to promote peace talks: former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, and former Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn.

The mediators brought credibility, expertise, and a pan-African mandate to the bargaining table, but failed to achieve any significant milestone in creating peace.

By March, Kinshasa was still adamant about not dealing directly with the M23 rebels, despite regional pressure.

The DRC administration said that granting them legitimacy at the negotiating table would compromise national sovereignty and accused the organization of serving as a foreign proxy.

This hardened position was reinforced even as global actors, such as the United Kingdom, called for inclusive dialogue involving all parties.

Angola was introduced as a new possible mediator on March 12.

DON’T MISS THIS: More fighting may break out in East Africa as Burundi’s president points to potential attackers

In contrast to previous diplomatic attempts that mostly ignored the rebel organization, it suggested direct talks between the Congolese government and the M23.

A few days later, on March 18, the Angola-led discussions collapsed as the M23 delegation left, blaming influence from other parties, mainly EU sanctions.

A week later, Angola formally ended its mediation role, preferring to focus on African Union initiatives.

Enter Qatar and the U.S.: A Diplomatic Pivot

By late March, a new round of negotiations sprang up, this time hosted by Qatar.

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda and President Félix Tshisekedi of the DRC met through Qatari mediation.

A joint statement issued by both parties, together with Qatar, acknowledged previous peace initiatives, notably the Luanda and Nairobi talks, and suggested a fresh push to engage diplomatically.

Qatar selected April 9 as the official date for the next round of peace negotiations in Doha.

As the new diplomatic impetus grew, the United States intervened more urgently.

By late April, US assistance had helped take discussions closer to a solid framework.

On April 25, in Washington, Rwanda and the DRC agreed to work toward a peace and economic cooperation deal, one that emphasized mutual respect for sovereignty and the creation of a comprehensive draft agreement by May 2nd.

Conditions for Peace

With diplomatic lines more active than ever, the U.S. began to demand harsher terms to move the process along.

Among these was the demand that Rwanda withdraw all of its military personnel from eastern Congo, a vital trust-building gesture viewed as non-negotiable by both Kinshasa and international observers.

Diplomats from the United States also requested guarantees about the cessation of cross-border funding for armed groups, verification procedures, and initiatives to foster economic growth in the eastern provinces, which have been neglected and destroyed by decades of turmoil.

Washington’s presence added weight to the discussions and helped alter the tone from antagonism to cautious collaboration.

July 31: A First Step in Implementation

The culmination of these efforts occurred on July 31, 2025, when Rwanda and the DRC hosted the first meeting of their Joint Oversight Committee in Washington.

This committee was entrusted with supervising the gradual implementation of the US-brokered peace deal.

This encounter signaled a watershed moment in the two countries’ long-strained relationship.

While tensions have not been completely resolved, and suspicions remain high, the establishment of a joint committee showed a mutual acknowledgment of the importance of structured, verifiable action.

It also showed the role of external diplomacy in pushing both countries toward responsibility and partnership.

Long Shadows and Lingering Questions

Even while these diplomatic breakthroughs provide some reassurance, the tasks ahead are severe.

The underlying grievances, land rights, ethnic conflicts, regional power struggles, and rivalry for mineral wealth have not magically gone away.

Similarly, trust between Kigali and Kinshasa is tenuous at best.

SEE ALSO: Farmers return to Congo farmland amid uncertain realities

One accord is unlikely to demolish the region’s decades-long history of proxy wars and changing allegiances.

Nonetheless, 2025 may be regarded as the year in which both parties made significant progress toward long-term peace.

While the path ahead remains undefined, and the conflict’s origins are deep, the formation of a Joint Oversight Committee and the US-backed framework for collaboration are significant steps forward.

Even cautious hope is worth sticking to in a region plagued by violence for so long.