Eswatini’s secretive deal with the United States to accept third-country deportees under President Donald Trump’s immigration programme has landed in court, with human rights lawyers and activists arguing that the agreement is unconstitutional.

- Eswatini entered a secretive agreement with the United States to accept third-country deportees, now facing legal scrutiny.

- The Eswatini Litigation Centre, supported by the Southern Africa Litigation Centre, has challenged the deal, claiming it violates constitutional protocols.

- Concerns have been raised over the lack of public disclosure and parliamentary approval for the agreement, casting doubts on its legality and transparency.

- The deal’s implementation has raised alarms among activists about potential risks to human rights and national security.

The case, brought by the Eswatini Litigation Centre, was set to be heard at the High Court on Friday but was postponed until September 25 after the government failed to file its response papers, according to Reuters.

Joining the Centre is the Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC), represented by its civic rights cluster lead, Melusi Simelane, who is also a co-applicant in the matter.

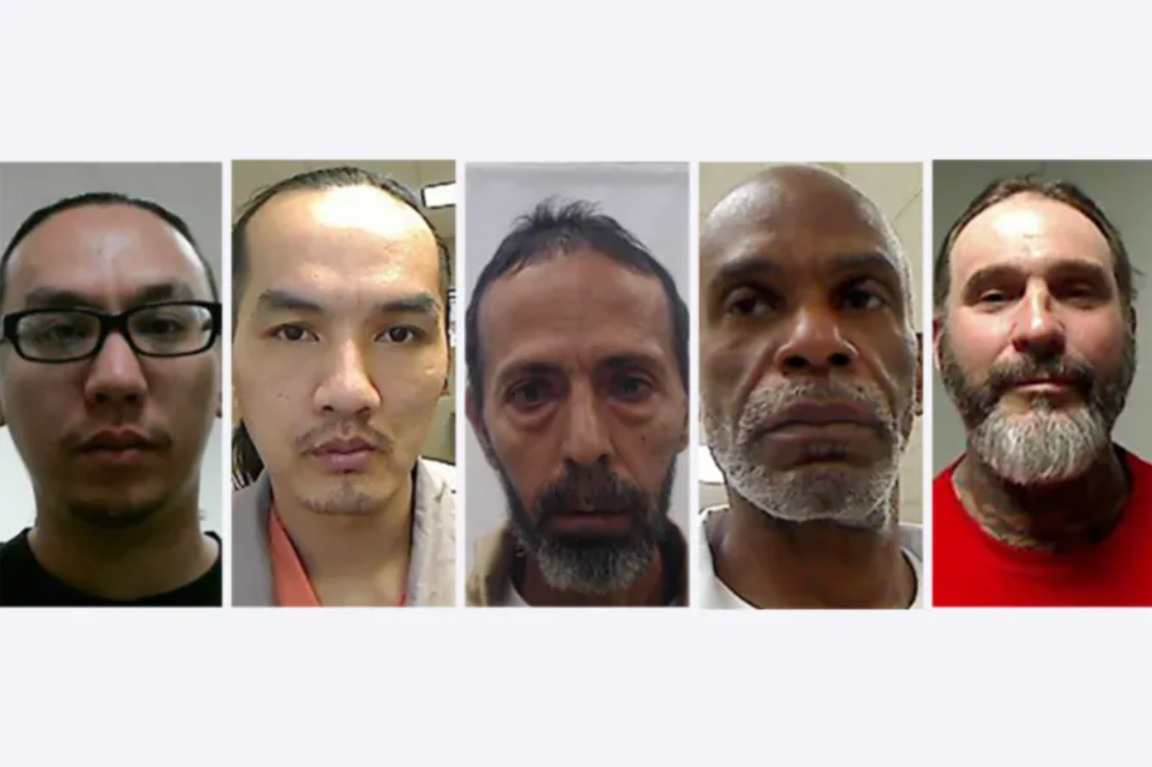

The legal challenge comes in the wake of the deportation of five ‘deadly’ individuals to Eswatini in July under the controversial agreement with Washington.

The arrangement, already implemented despite limited public disclosure, has triggered widespread condemnation from activists who question its secrecy and the risks it may pose to national security and human rights.

The applicants argue that the deportation pact is unlawful because it was never tabled before parliament for approval and its terms were withheld from the public.

“We want the executive to be held accountable, we want transparency dealing with matters of state importance, and respect for the rights of all individuals who are in Eswatini regardless of who they may be,” said lead applicant and lawyer Mzwandile Masuku.

Deportation deal legal, no cause for alarm

While responding to the legal challenge, Eswatini’s Attorney General Sifiso Khumalo dismissed the lawsuit in a text message to Reuters, describing it as “a frivolous legal application” with no legal basis.

The government has insisted that the deportees pose no security threat and that the deal was struck purely to reinforce Eswatini’s long-standing ties with Washington.

When the deportees were transferred in July, the government said the move was “the result of months of robust high-level engagements.”

Spokesperson Thabile Mdluli added that “the five prisoners are in the country and are housed in correctional facilities within isolated units, where similar offenders are kept.”

At the same time, Mdluli appeared to acknowledge human rights concerns, noting that accepting individuals whose countries of origin are not Eswatini raised sensitive issues.

“As a responsible member of the global community, the Kingdom of Eswatini adheres to international agreements and diplomatic protocols regarding the repatriation of individuals, ensuring that due process and respect for human rights is followed,” she said.

Mdluli also revealed that Eswatini would work with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) “to facilitate the transit of the inmates to their countries of origin.”

The case has placed Eswatini’s governance under scrutiny, shining a spotlight on Africa’s last absolute monarchy under King Mswati III, and raising wider concerns about transparency, accountability, and the human rights implications of secretive international agreements.