A day after Ethiopia inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Egypt has renewed warnings that the project poses a serious threat to its water security.

- Egypt warns the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) threatens its water security.

- The $5 billion GERD project is Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam, aimed at doubling Ethiopia’s power capacity.

- Ethiopia emphasizes its right to use its resources for economic growth and poverty alleviation.

The $5 billion dam, built on the Blue Nile, is Africa’s largest hydroelectric project and is expected to more than double Ethiopia’s power capacity.

But Cairo has long opposed it, describing the dam as a direct danger to the livelihoods of more than 100 million Egyptians who rely on the Nile River for nearly all their freshwater needs.

Egypt’s position

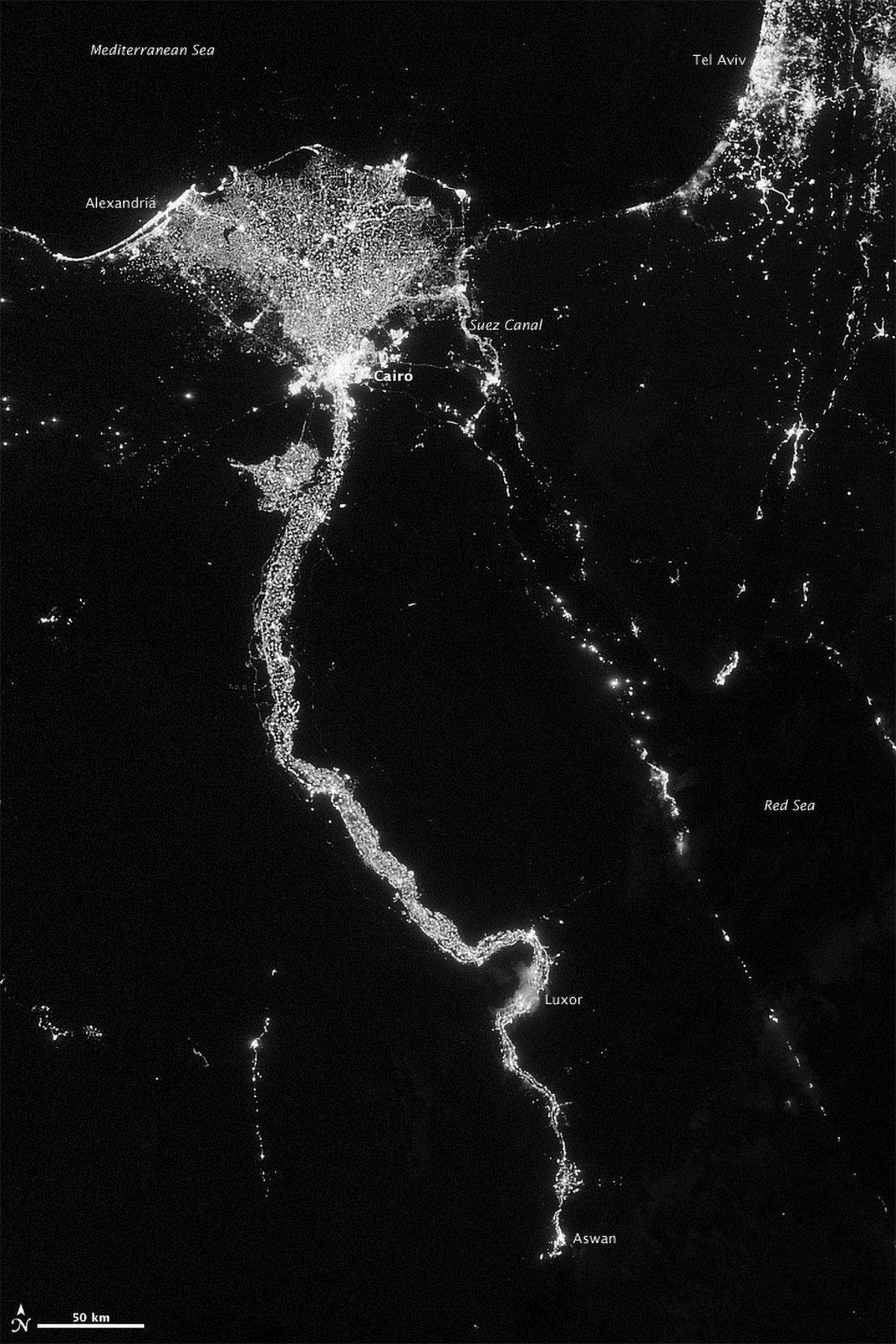

For Egypt, the Nile is more than a river; it is the country’s lifeline. Almost 95% of its people live along the Nile valley and delta, and the river provides the water needed for farming, drinking, and industry.

Any significant disruption in the flow could have devastating effects on food supplies and daily life. This is why Egyptian leaders have described the GERD as an “existential threat.”

Officials in Cairo argue that Ethiopia pressed ahead with filling the dam’s massive reservoir without proper consultation or a legally binding agreement.

Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs insists this violates international law, pointing to long-standing treaties that gave Egypt special rights over the Nile. These include the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement, which granted Egypt and Sudan a dominant share of the river’s flow.

Former members of Egypt’s assessment team have also raised the alarm.

Mohamed Mohey el-Deen, formerly part of Egypt’s team assessing GERD’s impact, told reporters that the GERD is not only about water but about stability.

“A major drop in supply threatens Egypt’s internal security. The stakes are economic, political, and deeply social,” he said.

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has repeated that Egypt will defend its rights to the Nile

Over the years, Cairo has taken the issue to the UN Security Council, appealed to international allies, and worked with the Arab League to raise pressure on Ethiopia.

Egypt also claims it reserves the right to use “all available means” to protect its water interests, though so far it has avoided direct confrontation.

Despite more than a decade of talks, no agreement has been reached on how the dam should be filled and operated.

Negotiations mediated by the United States, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and the African Union have all stalled.

Ethiopia maintains that it has the right to use its own resources to fight poverty and grow its economy, while Egypt insists on guarantees that its water supply will not be harmed.

The African Union has attempted to mediate in recent years, but its efforts have not led to a breakthrough. Observers say the core issue remains trust, and without compromise, the dispute risks dragging on for years.

Ethiopia’s response

Ethiopia has consistently defended the GERD as a symbol of national pride and development.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said during the inauguration that the project would never harm downstream countries.

“Ethiopia has no intention of harming anyone and wants the dam to be seen as a regional asset rather than a regional threat”, he declared.

Addis Ababa argues that the dam is essential to lifting millions of Ethiopians out of poverty.

The government says the GERD will change this reality by doubling national electricity capacity, boosting industries, and providing power exports to neighbours such as Kenya, South Sudan, and Tanzania.

“Ethiopia will never take away your rightful share. The hunger of our brothers in Egypt and Sudan is also our hunger. We must share and grow together.”

Ethiopia also points out that more than 90% of the project’s funding came from its own people, through state contributions, diaspora donations, and bond sales.

For many Ethiopians, the dam is a matter of sovereignty and proof that the country can pursue development on its own terms, without relying on foreign donors or lenders.

Why it matters

The Blue Nile contributes about 85% of the water that flows into the larger Nile River, which supports more than 250 million people across 11 countries.

For Egypt, which relies on the Nile for 95% of its water, the stakes are extremely high. For Ethiopia, the dam represents a once-in-a-generation chance to transform its economy.

The GERD therefore sits at the intersection of development and security. If managed cooperatively, it could power growth across East Africa and improve resilience against droughts and floods.

If not, it risks deepening mistrust between neighbours and fuelling one of the continent’s most enduring geopolitical flashpoints.